Table of Contents

What were the Windscale Piles?

The Windscale Piles were located in Seascale, Cumbria (now part of the Sellafield site). They were constructed as part of Britain’s post-war efforts for the production of the atomic bomb.

The two graphite “piles” were built between 1947 and 1951, with the intention of producing nuclear energy and plutonium-239 to use within nuclear weaponry; the piles commenced operations from 1950 and 1951 respectively.

How do the Windscale Pile reactors work?

The choice of fuel, moderator and coolant were constrained by the knowledge and technology available to the UK at the time. Therefore, the piles were designed around using natural uranium metal as their fuel because the UK was not yet able to carry out enrichment.

Fuel

Fuel

Moderator

Moderator

Coolant

Coolant

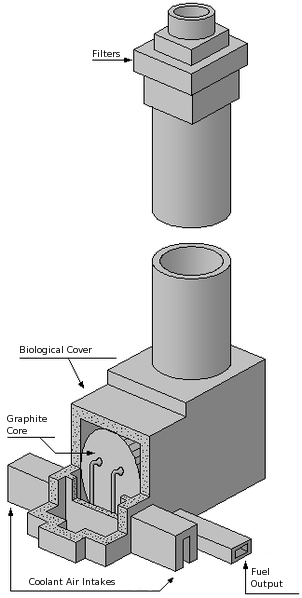

How was coolant air filtered?

The piles operated using an air-cooled system, with coolant air pulled down 120 m tall chimneys by convection (the tendency of hot air to rise due to its lower density). This resulted in a design that is efficient for smaller facilities but unfortunately increases the likelihood of releasing contaminated air into the atmosphere. To stop this risk, a respected scientist, named Sir John Cockroft, insisted filters were installed on top of the piles. Named after the scientist himself, “Cockroft’s follies” potentially saved countless people from absorbing dangerous radiation. We’ll mention this in more detail a little later on!

The Windscale Fire

Windscale Pile 1

Due to the pressures of the Cold War, in the early 1950s Britain’s government was heavily focused on ensuring the country was able to manufacture their own nuclear weaponry and keep up with countries around the world that could already manufacture their own nuclear weapons.

In October 1957, the explosion of an aluminium canister caused a uranium rod to catch fire inside the reactor. This rod continued to burn for three days and, overtime, set other rods alight. At its worst, nearly 11 tonnes of uranium were on fire; releasing radioactive materials every second it burnt.

Operators first tried to put out the fire by running fans at maximum speed – this caused the fire to escalate and grow. Finally, after 3 days of burning, the operators decided to turn off air flow to the burning uranium and thus the fire was extinguished.

What were the underlying causes?

From the beginning, there was heavy pressure from the government towards having an operating nuclear reactor over the safe construction and operation of the piles; this can be referred to as “production imperative”. One example of this is pile operatives cutting components to the size needed during the construction phase to ensure there were no delays – an action that would never be allowed in construction of a nuclear reactor nowadays.

“Production imperative” becomes more evident during the operation of Windscale; due to the immense pressure from the government the piles were producing plutonium above a level of which they were designed to operate at.

Too little, too late however as the fire had released a radioactive cloud into the eastern winds which spread the radioactive debris across the UK and Europe. Fortunately, Sir John Cockroft and his insistence on his “follies” prevented the Windscale incident from being dramatically worse and saved a considerable part of the Lake District and Cumbria! Regardless of this, the Windscale event was categorised as a level 5 (out of 7) on the International Nuclear Event Scale (INES) and still to this date it remains Britain’s worst nuclear event in history.

The uncontrollable radioactive debris had a huge impact on local agriculture, the government demanded that all local milk (produced within 300 square miles of the incident) was disposed of for the subsequent month.

Windscale Pile 2

Pile 2 remained undamaged by the fire, but was shut down soon afterwards. It has since been decommissioned.

The Nuclear Installations Act

Windscale is still the UK’s worst nuclear accident, at INES Level 5. This is due to the establishment of the UK’s independent nuclear regulator following the incident: the Nuclear Installations Inspectorate (NII) was initially formed under the Nuclear Installations Act 1959. By 1965, the Nuclear Installations Act 1965 (NIA 65) established the current licensing regime for nuclear licensed sites.

The NII has developed over the years, becoming the Office for Nuclear Regulation (ONR) in 2014, under the Energy Act 2013.

Throughout its history, the UK’s independent nuclear regulator has sought to ensure that nuclear facilities, including power stations, are operated safely throughout their lifecycle – including construction, operation and decommissioning. This includes consideration that any nuclear facility is safe for both people and for the environment.

Explore Further

Choose from the articles below to continue learning about nuclear.

Nuclear Energy – The Key to a Low-Carbon Future

Institute of Nuclear Power Operators – What does INPO stand for?

Pressurised Water Reactor (PWR) – The Most Common Nuclear Reactor

Nuclear Fuel Cycle – Enrichment

Did you know? Explore Nuclear also offers great careers information and learning resources.

Below you can find references to the information and images used on this page.

Content References

- Nuclear Development in the United Kingdom, World Nuclear Association

- Safety of Nuclear Power Reactors, World Nuclear Association

- Windscale fire – Wikipedia

- BBC – Cumbria – Places – The Windscale Fire

- Sixty-two years on – Cleaning up our nuclear past: faster, safer and sooner

- When Windscale burned – Nuclear Engineering International

- Windscale fire | Nuclear Disaster, Cumbrian Village | Britannica