Table of Contents

The Pressurised Water Reactor Story

The Pressurised Water Reactor (PWR) was first developed to power submarines; the initial research, development and design originated from Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the USA. Today, there are over 300 operational pressurised water reactors across the world, making the PWR by far the most prevalent reactor technology.

Development of the Pressurised Water Reactor Design

The first PWR, the Mark 1 Prototype Naval Reactor, was powered up in Idaho during 1953. The following year, 1954, the USA launched the first nuclear-power submarine: USS Nautilus. To this day, the pressurised water reactor is the backbone of the world’s fleet of nuclear-power submarines and surface vessels.

From its origins in naval propulsion, the PWR evolved to applications in civil nuclear power – supplying energy to electricity grids across the globe. The transition began in 1957 with an American prototype in Pennsylvania, the Shippingport Demonstration PWR. The first commercial PWR, Yankee Rowe Nuclear Power Station in Massachusetts, was commissioned in 1961. The analogous Russian design is known as the Vodo-Vodyanoi Enyergeticheskiy Reaktor (VVER, translating as the water-water power reactor).

Advantages and Challenges of a Pressurised Water Reactor

The pressurised water reactor design is a widely used and well proven technology. Their use of uranium dioxide fuel and a water moderator relies on an understanding of how to enrich uranium efficiently. A PWR possesses inherent thermal feedback, a passive safety mechanisms where an increase in coolant water temperature decreases the criticality of the reactor – failing to safe. Additionally, pressurisation of the water within the primary circuit minimises the risk of of water boiling inside the reactor core.

Compared to AGRs, PWRs have a lower thermal efficiency of 34 % (compared with 41 %). PWRs also have a much smaller reactor pressure vessel than both AGRs and Magnox Reactors and, thus, a greater power density; this is due to their use of water as both coolant and moderator.

Legacy and Decommissioning

Whilst most of the world’s pressurised water reactor fleet are still generating power (including life extensions of up to 80 years!), some have entered the decommissioning phase of their life cycle.

How does a Pressurised Water Reactor work?

A pressurised water reactor is a type of water-cooled, water-moderated nuclear reactor that uses uranium oxide as fuel, enriched to 3-5% uranium-235. By acting as a moderator, the water slows down neutrons to sustain the nuclear chain reaction.

In a PWR, the reactor’s primary cooling circuit contains water which acts as a coolant by circulating through through the reactor core to transfer heat from the fuel rods to a steam generator. Water in the primary circuit is hot, around 300°C, and is prevented from boiling by being kept at high pressure.

A PWR’s secondary circuit also uses water as a coolant. Water in the secondary circuit is under less pressure and therefore boils after interacting with the heat exchanger, which is held inside the Steam Generator. The steam from the boiled water is used to turn the turbine to generate electricity.

How does a Pressurised Water Reactor compare?

A pressurised water reactor has inherent thermal feedback, a form of passive safety where an increase in coolant water temperature decreases the criticality of the reactor – failing to safe. The reason for this is that as temperature increases, water density decreases and so the water becomes a less effective moderator; this reduces the rate of nuclear fission, decreasing the temperature. This is a key reason why PWRs are so safe and widely used.

Compared to AGRs, each pressurised water reactor has a smaller reactor pressure vessel and thus a greater power density.

Uranium Dioxide Fuel

The fuel rods used in a pressurised water reactor contains uranium dioxide powder, enriched to 3-55% uranium-235 and pressed into pellets. A typical PWR fuel assembly contains fuel rods in a 17 x 17 grid, each comprising many uranium dioxide pellets and clad in a zirconium alloy.

PWRs can last between 18-24 months without being refuelled! At each refuelling cycle, the reactor is shut down and approximately one third of the fuel is replaced; the remaining fuel is rearranged to optimise burn-up.

Zirconium Alloy Cladding

The cladding on each pressurised water reactor fuel rod must be able to withstand high temperatures of up to 300oC, without brittle fracture or corrosion. Therefore, a zirconium alloy was chosen as the cladding material for use on PWR fuel rods. Zirconium alloy was chosen due to its exceptional corrosion resistance and relatively low cross-section for neutron absorption.

Water Moderator

A pressurised water reactor uses light water, typically containing a small concentration of boron, as the moderator. Combined, these allow operators to control the extent to which neutrons are slowed down, and therefore control the rate of the nuclear fission reaction and the power output of the reactor.

This, along with the mechanism of thermal feedback, contributes to a PWR’s reliability and safety.

Although control rods can also be used to control the amount of fission that happens, unlike in a Magnox reactor or AGR, in a pressurised water reactor the control rods are typically only used to shut down the reactor.

Water Coolant

A pressurised water reactor also uses its water (H2O) as a coolant. Within the primary circuit, this water is prevented from boiling by being kept at high pressure, typically 16 bar. The pressure in the primary circuit is controlled by the Pressuriser, which ensures the cooling water stays in a liquid state. The Pressuriser is a separate vessel connected to the primary circuit. It contains water and steam at a typical pressure of 16 bar, controlled by changing the temperature inside the pressuriser. Temperature control within the pressuriser is achieved by either water being sprayed in to cool it down or electric heaters being used to heat it up.

Hot coolant gas is then used to produce steam in the secondary circuit’s steam generator, exchanging heat with cold water. Simultaneously, as it transfers heat, the water cools back down so it can recirculate and remove more heat from the nuclear reactor core. Meanwhile, the water fed to the steam generator is heated up sufficiently high that it evaporates and forms high energy steam. It is this steam that uses its kinetic energy to drive turbines that generate electricity. The steam then enters the condenser, condensing back to liquid water.

Safety Features of a Pressurised Water Reactor

In addition to passive safety via thermal feedback a PWR has a number of additional safety systems, including:

- A scram is a sudden reactor shutdown used in an emergency scenario. The control rods are dropped into the reactor core and stop the fission reaction occurring. The fuel will still give off decay heat so must be cooled.

- If the reactor loses coolant due to an accident, the coolant must be replaced so that the reactor does not over heat. This involves many systems such as high pressure coolant injection system, containment spray system, and isolation cooling system.

- A key safety feature of a PWR is the containment shielding that surrounds the primary circuit. This stops any radiation getting to the outside environment, and also is reinforced to stop things getting in. This includes extreme weather events like hurricanes, missiles and even stops planes from crashing through it!

Decommissioning a Pressurised Water Reactor

The Decommissioning Process

Whilst many Pressurised Water Reactors are still generating power and have even had life extensions up to 80 years, decommissioning is the next stage of the nuclear life cycle and some reactors have already entered the decommissioning phase.

The decommissioning strategy of a typical PWR will follows the following structure:

- Defueling: This process is expected to take 3-10 years, whilst the spent fuel from the reactor is removed and stored in cooling ponds. This stage handles 99% of the radioactivity on the entire site.

- Deconstruction of the Site: This process will take 10-15 years where all non-essential buildings (excluding the reactor) and structures are decontaminated and deconstructed.

- Safe Store Period: The remains of the site such as the reactor will be left covered for 70-85 years while the activity level naturally drops to much safer levels.

- Final Destruction: This process will take roughly 10-15 years were all remaining equipment, such as the reactor, is dismantled and processed.

- Final Remediation: After all equipment and building have been deconstructed and disposed, final clean up takes place restoring the site back to the green field it once was.

Challenges

Safety: Ensuring the safety of workers and the public is paramount. Strict safety protocols and continuous monitoring are essential to prevent radiation exposure and accidents.

Technical Complexity: The decommissioning process involves intricate engineering challenges, particularly in dismantling radioactive components and managing waste.

Cost: Decommissioning is a costly endeavour and a ring-fenced budget for decommissioning is typically allocated.

Time: The entire decommissioning process can take several decades.

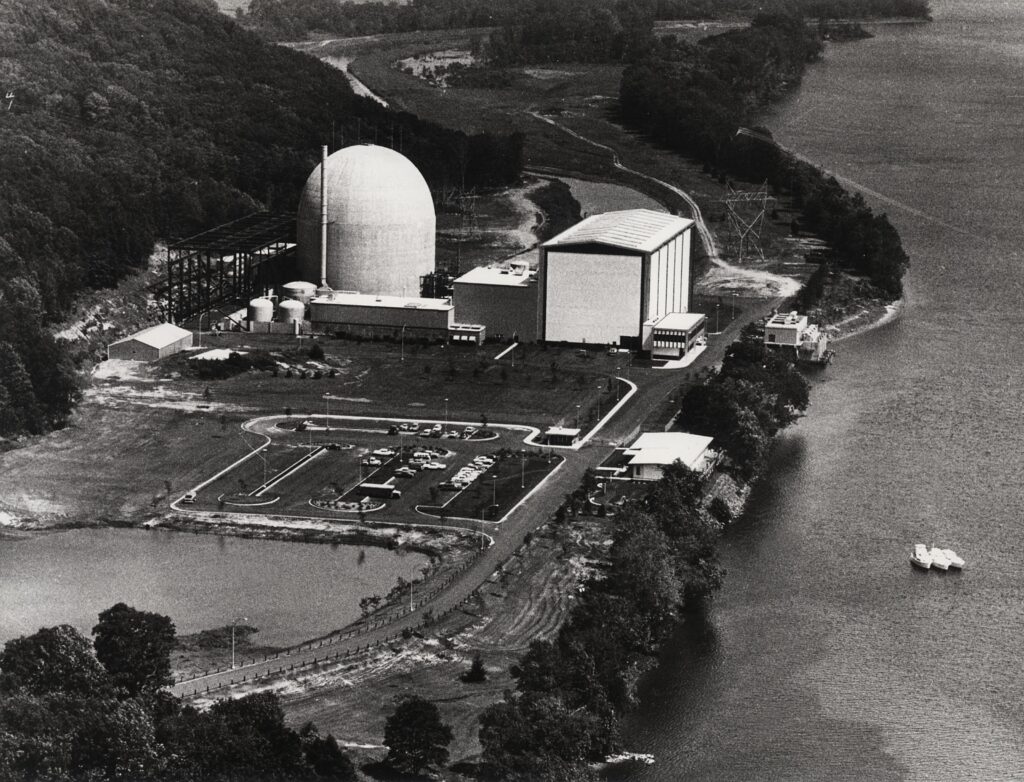

Case Study: Connecticut Yankee

Connecticut Yankee Nuclear Power Plant was a Westinghouse-designed pressurised water reactor in the USA. The single reactor site was commissioned in 1968 and generated electricity for almost thirty years, before ceasing operations in 1996 due to the 582 MWe reactor unit no longer being cost effective to run.

Decommissioning of the majority of the site was complete by 2004, with the reactor containment dome demolished during 2006. Spent fuel remains on a portion of the site for long-term storage, prior to final disposal in a Geological Disposal Facility. The remainder of the site has been fully remediated and is ready for reuse.

Explore Further

Choose from the articles below to continue learning about nuclear.

Sodium-cooled Fast Reactor (SFR) – a Fast Future for Fission?

Lead-cooled Fast Reactor (LFR) – from Metal to Megawatts

High Temperature Gas Reactor (HTGR) – Innovation in Prisms & Pebbles

Magnox Reactors – At the Forefront of a New Age

Did you know? Explore Nuclear also offers great careers information and learning resources.

Below you can find references to the information and images used on this page.

Content References

Image References

- Sizewell B Power Station – Simon James – CC BY-SA 2.0

- Exelon Three Mile Island Nuclear Generating Station – Constellation Energy – CC BY-SA 4.0

- Cruas Nuclear Power Station, France – Iodama – CC BY-SA 3.0

- Vogtle NPP – US NRC – Public Domain

- Hinkley Point C (Visualisation) – Gov.UK – Open Government Licence V3.0

- Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant – Tracey Adams – CC BY 2.0

- PWR Nuclear Power Plant Diagram – Tennessee Valley Authority – Public Domain

- AGR fuel pin, about 1958-1982 – Science Museum Group – CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

- Water Bubbles – Pexels – CC0

- Robinson Nuclear Station seen from Lake Robinson – Murr Rhame – CC BY-SA 3.0

- Centrale nucléaire de Saint-Alban Saint-Maurice – SashiRolls – CC BY-SA 4.0

- Connecticut Yankee Nuclear Power Plant – US DOE – Public Domain